In the land where myths and beliefs are rooted and where history was created, there exists a war that is as enduring as the land itself. What if the real history of the conflict is not only in the loud clashes we read, watch, or hear about, but in the voices of the rarely heard? Yes, the Israel-Palestine conflict is one of the oldest and most challenging conflicts in contemporary world politics. For a true perception of the conflict to be realized, one has to navigate the narratives of the official or majority discourse the voices and narrative excluded or ignored. This is why the theory of subaltern realism provides the proper and intriguing perspective through which to undertake the extended research of this battle.

The Israel-Palestine conflict is often framed as a straightforward clash between two opposing sides: On the one side there are the Israelis who are determined to find safety and sovereignty for their people and on the other side, there are Palestinians who struggle for their rights to independence. But what lies behind such general tendencies? The root cause of the conflict can be viewed in the Zionist political movement starting in the last part of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth with the establishment of the Palestinian state. It emerged after World War I, especially after the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which called for ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’. This led to the formation of Israel in 1948, which was a cause for celebration for Jews across the world but a disaster for Palestinians, a term they use to refer to the disaster or Nakba.

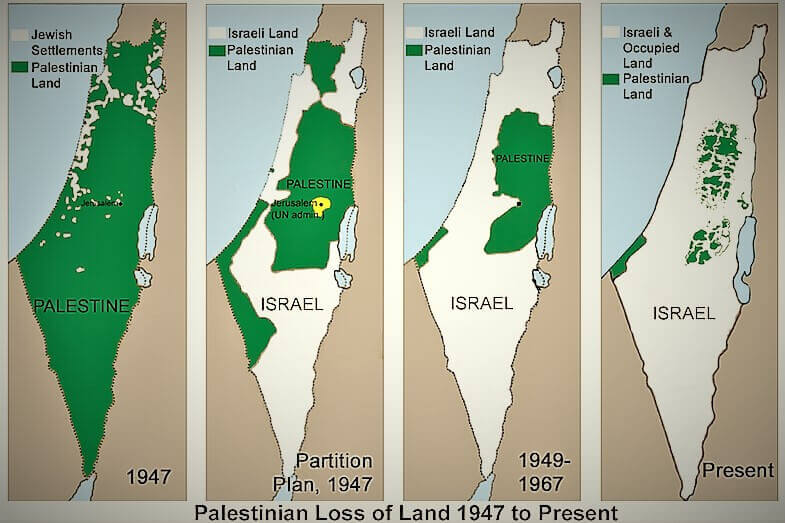

To Palestinians, the Nakba was the first step of a process of displacement that has become chronic. The conflict led to the displacement of more than 700,000 Palestinians most of whom to this day are refugees in neighboring countries or the West Bank and Gaza Strip area. Palestinians are still resenting this displacement as the territorial division remains a significant aspect of their identity and the motive for their fight. However, even in Palestinian society, there are many opinions, ranging from advocating for the use of force and the armed uprising to advocating the pillage and nonviolent protest, as well as the demand for a two-state solution. They are drowned out by the main narrative of the struggle against the occupation of Israel or Palestine depending on the side people support.

The Israeli narrative is also not less complex than that of the Palestinians. The appearance of Israel was considered as the realization of the dream of the Jews which they had lived for hundreds of years, namely the dream to return to their historical homeland. But this dream came with Challenges for instance; security was a big issue in a region that could not be neglected. The basic theme of conflict is deep-rooted in the issues of the state of Israel fulfilling the security needs of its public after several events like the six-day war in 1967 where Israel took control of West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem –hot and strategic territory’s up to this very age. The continued occupation and destruction of these regions has therefore attracted the ire of the international community and it has made it even more difficult to negotiate for peace with Palestinians.

Still, this message can also be heard within Israel, although such voices remain relatively marginal in the country. To know more about the experience of Arab Israelis, who are estimated to be 20% of the population, one has to concentrate on aspects of Jewishness. Organizations, such as B’Tselem; an Israeli human rights NGO, document violations of human rights of Palestinians under occupation and campaign for rights for the oppressed. All of these voices may be marginalized within dominant forms of ‘official’ and ‘insider’ interpretations and representations of the conflict, but they are no less important for that.

There exists a postcolonial theory, Subaltern realism through which these oppressed marginalized voices and narratives can be heard or given a right to live. It opposes mainstream theories of international relations that tend to exclude consideration of the subordinate actors or pay attention to them only as much as they are acted upon by others. For instance, Palestinian refugees’ stories of living in camps are counterhegemonic to abstract stories of the conflict. These camps have been in existence for a long time, are overpopulated, and have very few resources in terms of infrastructure and basic amenities. But they are also key spaces where political and cultural processes take place, and where discourses of opposition and agency emerge. Even though these camps remain isolated from the WEST and the inhabitants of these camps have little input in any international discussions about the conflict, they offer a vital demographic in helping shape the Palestinian society.

Likewise, there are subordinate communities in Israel whose voices are not heard as directly or as loudly as others. On aspects like housing, employment, or education, Arab Israelis report discrimination and thus there is a different perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than the one of the Jewish majority. A significant portion of the Arab citizens in Israel want to have a state where Jews and Arabs will coexist in equality, which is contrary to the aims of Zionism. Listening to them makes one understand that there is also an Israeli side of the story and that peace needs to be broader in its perspective.

The view that the Israel-Palestine conflict is not merely a contest for land or rights to self-determination, but a fight for existence – an identity is being highlighted above. Subaltern realism is neither a guardian angel nor a solution. The vicious circle of Israel Israeli-Palestinian conflict is rooted deeply in the religious, historical, and geopolitical aspects through which no single theory can represent its complexity. To understand the stories not usually told—those of the Palestinians living in camps, Arabs living in Israel demanding equal rights, or Israelis protesting occupation and prejudice—one must tune in different frequencies. The focus on stories and subjects’ experiences can sometimes become a challenge and obscure the conflict and develop solutions to the same. But it is exactly in this sense that subaltern realism provides an opportunity to move beyond the general understanding of the conflict and its characters as simply those of the righteous and the evil, the occupiers and the occupied.

Muti Ur Rehman

Muti Ur Rehman is a research student pursuing his bachelors in Strategic Studies from National Defence University, Islamabad.

- This author does not have any more posts.