While Chinese President Xi Jinping has stated that he would not hesitate to use force to achieve unification with Taiwan if necessary, the prospect of simultaneous conflicts in East Asia—one in the Taiwan Strait and another on the Korean Peninsula—is no longer far-fetched. A core strategic concern for the United States, Japan, and South Korea is that the current regional security architecture—namely, the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (1960) and the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty (1953)—may prove inadequate in effectively addressing a two-front war scenario.

This challenge has been further compounded by the inauguration of a U.S. president who has shown a tendency to downplay Washington’s defense commitments under certain conditions, raising serious concerns among allies about the credibility and timeliness of a U.S. military response in the event of a major regional crisis.

In this article, I propose four key measures that would better prepare U.S. allies—specifically Japan and South Korea—to respond more effectively to dual contingencies, thereby strengthening regional deterrence and defense resilience.

Recommendation One: Enhance Strategic Alignment Between Japanese and South Korean Defense Postures

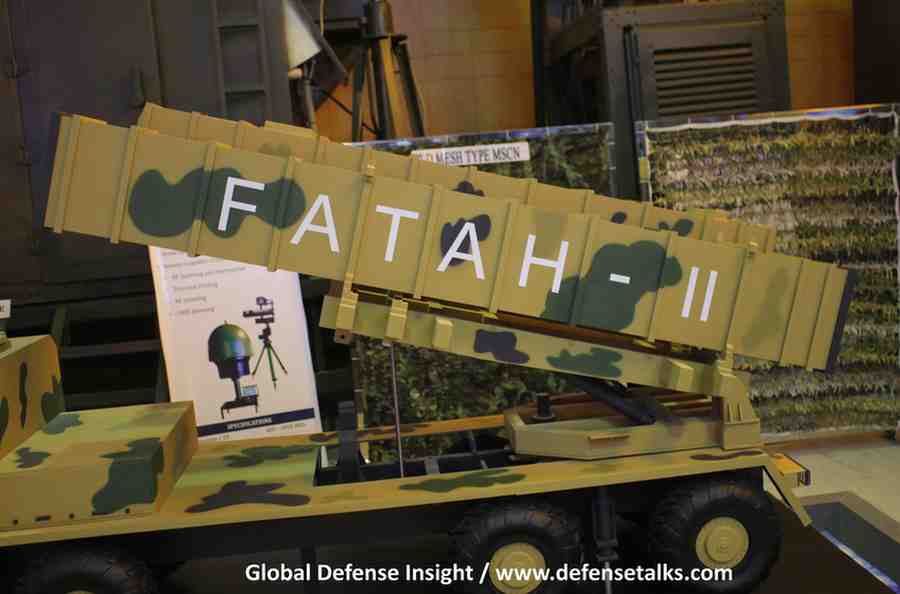

To more effectively counter the North Korean threat, South Korea has developed a comprehensive deterrence framework known as the Three-Axis System, comprising Kill Chain (preemptive strike capability), KAMD (Korea Air and Missile Defense), and KMPR (Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation). Meanwhile, in 2022, Japan announced a historic shift in its defense policy by committing to acquire an enemy base strike capability, marking a significant expansion of its strategic reach.

In the event of a two-front war in East Asia—simultaneous conflicts in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean Peninsula—U.S. military assets would be stretched thin, unable to fully concentrate in both theaters. This underscores the urgent need for greater synergy between Japanese and South Korean defense mechanisms, to ensure efficient use of available national resources and to bolster collective deterrence.

Given that a large portion of Japan’s air and naval forces, along with U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ), would likely be deployed to support operations in the Taiwan Strait, U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) and the ROK military would bear primary responsibility for defending the Korean Peninsula against North Korean aggression. Under such conditions, it would be highly advisable for South Korea to integrate its Kill Chain system with Japan’s emerging enemy base strike capability—for example, through coordinated target allocation and information sharing.

Similarly, aligning South Korea’s KAMD system with Japan’s missile defense architecture would allow both countries to more efficiently manage and neutralize incoming missile threats from North Korea, reducing duplication and conserving critical interceptors. This level of operational integration would not only increase the effectiveness of both countries’ defense postures, but also enhance deterrence by denial, signaling to Pyongyang that any aggression would face a coordinated and overwhelming response.

Recommendation Two: Interpret the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty with Greater Strategic Flexibility

When the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty was signed in 1953, it was crafted in a vastly different strategic context—one focused almost exclusively on deterring and responding to a North Korean invasion of South Korea. As a result, U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) were primarily composed of fixed-position ground units, designed for territorial defense. In contrast, U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ) were structured with more expeditionary capabilities, including air, naval, and Marine elements that could be rapidly deployed beyond Japan’s borders.

Given the growing possibility of a two-front conflict—one on the Korean Peninsula and another in the Taiwan Strait—it is necessary to reinterpret the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty to reflect today’s complex security environment. This could be achieved through either a formal revision of the treaty or the establishment of a new bilateral framework, similar to the U.S.-Japan Defense Guidelines, that allows for a more flexible and forward-leaning interpretation of the alliance’s scope.

Specifically, incorporating the Taiwan contingency into the operational planning of the U.S.-ROK alliance would allow for greater strategic coordination. Under such a framework, USFK—and potentially certain South Korean military assets—could be deployed to assist in the defense of Taiwan, if China were to initiate hostilities. While it remains uncertain whether simultaneous wars in both theaters would occur, a sequential escalation (with a time gap between crises) is plausible. In such a case, a more flexible interpretation of the alliance would enable the U.S., Japan, and South Korea to reallocate and sequence their military assets more effectively—similar in concept to the strategic resource flow envisioned in the Schlieffen Plan, albeit adapted for a modern, multi-theater contingency.

Recommendation Three: Integrate Like-Minded Partners into the Regional Security Framework

Even with the implementation of Recommendations One and Two, the inherent limitations of available military resources cannot be fully overcome. One way to mitigate this constraint is to incorporate like-minded third-party partners into the regional security architecture to provide additional support and strategic depth.

While the United States, Japan, and South Korea would remain the primary actors in any East Asian contingency, countries such as Canada could play a meaningful supporting role. For example, Canada could enhance its collaboration with the United States through the modernization of NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command), thereby strengthening North American defenses against potential North Korean missile threats.

In parallel, Canada could align its intelligence and missile defense cooperation with South Korea, particularly by sharing real-time data on missile trajectories and contributing to joint early warning systems. Such contributions would not only enhance regional missile defense interoperability, but also reinforce nuclear deterrence posture against North Korea. This could help dissuade Pyongyang from pursuing nuclear decoupling strategies aimed at weakening the cohesion and credibility of the U.S.-Japan-ROK alliance framework.

By expanding the coalition to include trusted, capable partners like Canada, the trilateral alliance can bolster its deterrence posture, improve strategic resilience, and reduce operational strain across simultaneous contingencies.

Recommendation Four: Consideration of a Minimum Nuclear Deterrent for South Korea

As a measure of last resort, South Korea could consider developing a limited nuclear deterrent to counteract North Korea’s growing nuclear coercion and efforts to decouple the U.S. from its regional allies. Possessing an indigenous nuclear capability—carefully calibrated and clearly framed within a minimum deterrence posture—could raise the strategic costs for Pyongyang in contemplating a full-scale conflict against the South.

The existence of a credible South Korean nuclear deterrent would likely complicate North Korea’s war calculus, potentially deterring escalation on the Korean Peninsula and forcing Pyongyang to reassess the viability of initiating simultaneous regional conflicts. This could, in effect, limit the outbreak to a single theater conflict—such as in the Taiwan Strait—thereby reducing the overall burden on U.S., Japanese, and South Korean military resources.

To avoid provoking broader regional instability, South Korea’s nuclear arsenal should remain deliberately limited—no more than 30 warheads, well below North Korea’s estimated stockpile of 50. This force would focus on securing a credible second-strike capability, ensuring survivability and deterrence while avoiding the perception of seeking nuclear parity. A restrained posture would also reduce the likelihood of triggering alarm or aggressive countermeasures from neighboring nuclear powers, particularly China and Russia.

While such a step would carry significant diplomatic and nonproliferation implications, it reflects the urgent need to confront a deteriorating strategic environment—especially if alliance commitments weaken or extended deterrence becomes less credible in the eyes of U.S. allies.

Conclusion

Given the limitations of the United States’ current ‘One-Plus’ Strategy—which focuses on preparing for a major conflict with China while simultaneously deterring opportunistic aggression from other actors such as North Korea—it is increasingly evident that this framework may be insufficient to manage multiple, simultaneous large-scale conflicts. This concern is particularly acute in scenarios involving concurrent crises in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean Peninsula. The strategic challenge would be further compounded should a third front emerge, for example, in the Middle East involving a hostile Iran.

In view of these constraints, there is a pressing need to adopt a more resource-efficient strategy that proactively incorporates like-minded third-party partners into a broader regional security architecture. Although the potential acquisition of nuclear weapons by South Korea—as outlined in Recommendation Four—remains a highly sensitive and unlikely course in the near term due to significant diplomatic and legal implications, Recommendations One, Two, and Three present actionable pathways. These should be pursued either sequentially or in parallel, contingent on the evolving security environment.

By embracing a more integrated and collaborative approach, the United States, Japan, and South Korea—three longstanding democratic allies—will be better equipped to preserve the regional order that has underpinned peace, economic prosperity, and democratic consolidation in Northeast Asia for over seven decades.

Dr. Ju Hyung Kim

Dr. Ju Hyung Kim serves as President of the Security Management Institute, a defense-focused think tank affiliated with South Korea’s National Assembly. He has contributed to numerous defense initiatives and has advised key institutions, including the Republic of Korea Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Dr. Ju Hyung Kim#molongui-disabled-link

- Dr. Ju Hyung Kim#molongui-disabled-link

- Dr. Ju Hyung Kim#molongui-disabled-link

- Dr. Ju Hyung Kim#molongui-disabled-link