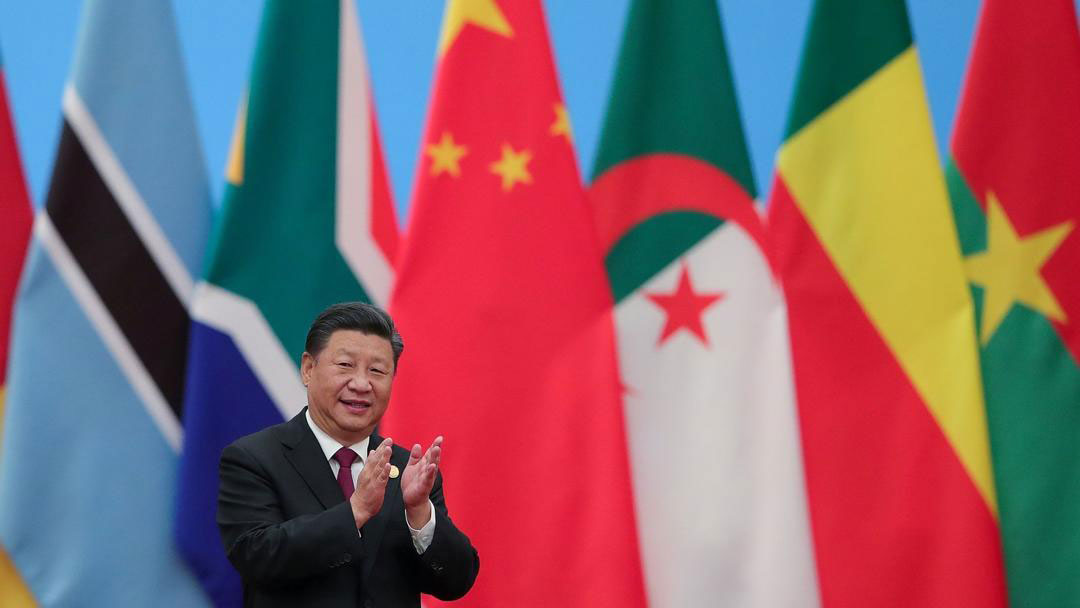

As a part of Washington’s “Beijing as the axis of evil” narrative, there have been persevering assaults on China’s multi-billion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with claims of “debt trap diplomacy” – strategically catching beneficiary nations with loans they can’t reimburse and utilizing it to accomplish geopolitical goals. China grants tremendous loans to monetarily weak states. The heavier the loan burden on the borrower, the more prominent China’s own leverage becomes, gradually turning into its economic master.

While Chinese loaning has contributed to debt over-burden in certain economies, it isn’t the driving force behind their concerns. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, for instance, is frequently depicted as the case second to none for China’s debt trap diplomacy. The record is that China loaned cash to Sri Lanka to construct the port, knowing that Colombo would encounter debt trouble and Beijing could then seize it in exchange for debt relief, allowing its utilization by China’s naval force. Contrarily, the venture was proposed by previous Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, not Beijing, as a feature of his administration’s impractical development program. It immediately turned into a “white elephant”, however, creating huge surplus capacity and adding to Sri Lanka’s monetary hardships. Sri Lanka’s debt distress emerged not from Chinese loans, but rather from extreme acquiring on Western-overwhelmed markets. Besides, of more than 3,000 Chinese-supported projects followed by different researchers, Hambantota is the solitary case of asset seizure. Data shows that asset seizures are the exemption, not the standard.

Particularly, as the instance of Hambantota Port shows, beneficiary nations play a major role in molding the BRI. China’s development financing is recipient-driven, and China basically can’t compel different countries to accept projects on their territory. Except if beneficiaries permit Chinese SOEs to attempt projects, secure their activities, and endorse the credits funding their work, BRI projects will not go for it. Normally, beneficiaries need projects that serve their interests, molded by need, greed, or both. There is little proof of Chinese procedure, however, a lot of proof of poor administration on the beneficiary side.

Conclusively, the debt trap claims are essential for what I contend are “infrastructure wars” all fed into a much bigger U.S.- China rivalry including the world’s two greatest economies. In the meantime, it is developing country administrations, and their related political and economic interests themselves, that decide the nature of BRI projects on their territory. This is the BRI’s reality – muddled and fragmented.

Author:

Komal sundri is pursuing her bachelor’s in International Relations from the National University of Modern Languages (NUML). Her writing pieces demonstrate her keen interest in the diplomatic and political order of South Asia and the Middle East while she keeps an eye on Maritime Politics.The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Defense Insight.