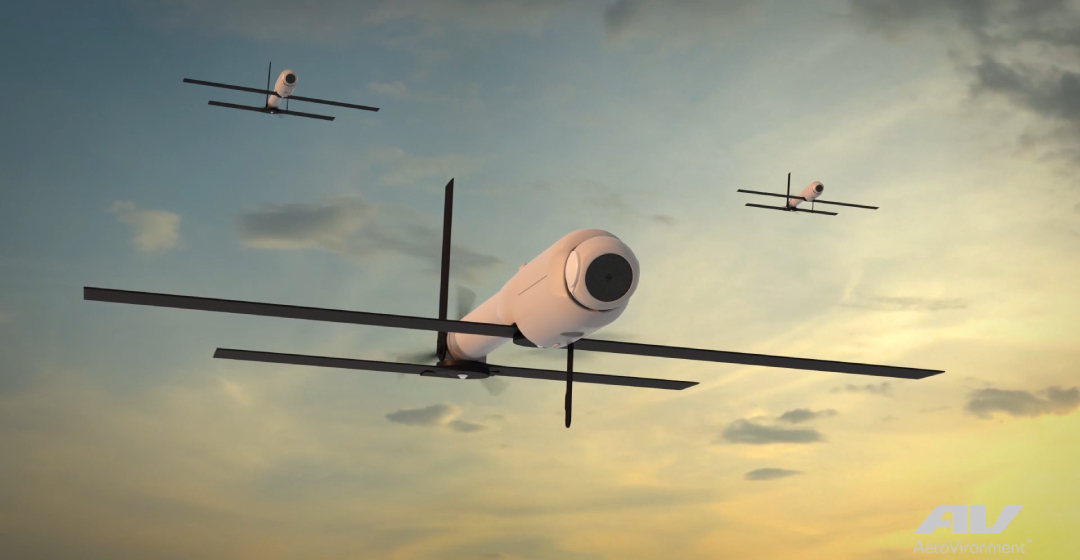

Imagine an army, a solid military brute force with a column of advanced tanks, flanked by mobile air defence systems and armoured personnel carriers, rumbling through the dense forest somewhere in Eastern European plains. Suddenly, the tranquillity of the forest was shattered by the high-pitched whirring of small drones. Swiftly, the drones descended upon the convoy, unleashing a barrage of firepower. The soldiers frantically tried to retaliate, but the tiny drones were agile and elusive, dodging the tank’s large calibre artillery. Even small MANPADs failed to counter this swarm. High-calibre anti-air rounds could do little after being overwhelmed by the sheer number of drones. One by one, the army tanks were disabled, and their defences were no match for the relentless precision of the drones. The once unstoppable convoy now lay in ruins, a sobering reminder of the evolving nature of modern warfare. This single event resulted in equipment costing hundreds of millions of dollars to be taken out by small, technologically inferior, makeshift drones that would barely cost a fraction of the equipment they destroyed.

The scenario mentioned above is not from any Sci-Fi movie or a war-themed game; this has occurred multiple times on actual battlefields in the last few years. Military observers around the world are drawing up their lessons from Ukraine, where Russia’s numerically superior forces faced defiant yet inventive resistance from Ukrainians. The war of territorial acquisition has become more of a “war of innovation”, serving as a stark lesson in the asymmetry of warfare, highlighting how small, nimble adversaries armed with advanced technology could pose a grave threat to even the most robust and well-equipped militaries. Hence, even Russia is innovating the use of AI-operated drones to make up for scattered operations in Ukraine. More recently, wired FPVs emerged on the Ukrainian battlefield ( to circumvent the issue of electronic countermeasures). The lesson entails that it is not just the size and strength of the arsenal that determines victory but the adaptability and resourcefulness to counter unconventional threats.

From the conflicts in Nagorno Karabakh and Libya , where Turkish drones re-defined battle dynamics, even fielding autonomous drones, to Israel, where IDF used thousands of drones to trace, identify and even execute target acquisition against human targets, drone warfare has come a long way. Turkish drones became a tool of “drone diplomacy “for Ankara, where its famed TB-2 system proved its battle worthiness at a fraction of the cost of American and European systems. Small militias and even armies are fielding more miniature First Person View ( FPV) drones as their go-to weapon, displacing the role of artillery, anti-infantry and, at times, anti-armour weapons.

The cost dividend makes these platforms lucrative as they do not require a robust industrial base, hefty cheques or even staggering manpower dedicated to operating single platforms. To give a perspective over cost dividend, after the Israeli strike on the Iranian embassy in Damascus, Syria, Iran responded by sending an attacking volley of hundreds of UAVs and cruise and ballistic missiles in what Tehran called Operation True Promise. Israel, its Western allies and Gulf states managed to counter most of the projectiles coming from Iran. Reuters reported that this attack would have cost Iran around 80 to 100 million dollars, while the bill for Israel and its allies stood at a staggering $1 billion to repel incoming projectile . A similar was the case when Houthis attacked Saudi Arabia through makeshift missile projectiles. At the same time, the kingdom had to counter these using a pricy Patriot missile defence system, where each missile costs around four million dollars.

The pace of modern warfare is commonly depicted as rapidly outpacing the need for human direction in operations or vehicle operations, rendering these roles obsolete. The primary concern is that military bureaucracies, entrenched in long-standing operational doctrines, are simultaneously enamoured by state-of-the-art technology. This may result in acquiring numerous cutting-edge platforms while steadfastly clinging to traditional operational principles.

The use of unmanned weapons is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, they are undeniably cost-effective. Drones are significantly cheaper than traditional military jets. For example, an MQ-9 Reaper drone costs only a fraction of the price of any manned American Fighter Jet, such as an F-15. The same is true for China, where its Wing Loong drone systems are way cheaper than its mainstay arsenal of fighter jets ( J-20 and J-11Bs). Even a basic first-person-view drone can be obtained for a few hundred dollars. In Ukraine, a team of ten such drones effectively neutralized Russian tanks costing in millions of dollars . In fact, over the past few months, more than two-thirds of the Russian tanks destroyed by Ukraine fell victim to these drones. This affordability enables states to deploy swarms of drones for surveillance or attack without any concern for losses. These swarms could easily overwhelm existing air defence systems, which are not designed to handle simultaneous attacks from hundreds of drones. Even if defence systems are successful, the cost of defending against swarms will far exceed the cost of the attack for the enemy.

In June 2024, an advanced Russian Stealth aircraft SU-57 was reported to be damaged beyond repair by a Ukrainian drone attack on an airbase in Southern Russia. To bring into perspective, the SU-57 is the latest and most expensive fighter jet in Russian inventory, tasked for special stealth operations. It is a system that would have countered any aircraft in Western inventory in an aerial dogfight, yet it found itself in the crosshairs of small, cheap drones while resting on the tarmac. Ukraine has showcased its ability to strike expensive, sophisticated systems ( such as mobile SAMs).

It is imperative to understand that modern militaries, realizing the threat and potential of this system, are rushing to reorient their military SOPs and structure to adapt to these developments. Last year, the United States unveiled its ambitious “Replicator “program, which entails mainstreaming loitering munitions in military operations. China has also presented its drone programs as it already leads the market for commercial-use small drones ( which have been used in multiple conflicts worldwide). China is even proceeding forward in utilizing AI to direct its drone warfare doctrines. Lessons from AI simulations would construe instructional doctrines for human commanders in case of real-time conflicts.

Small UAVs are not just an incentivizing weapon for militaries but even more for Non-state actors. Essentially, these outfits resorted to small arms or, at most, lethal explosives ( car bombings or improvised explosives) to achieve their goals. Open market access to quadcopters, similar systems, and improved remote guidance opens possibilities for such outfits. This was already witnessed when insurgent groups in Syria used improvised drones against Syrian and Russian forces. Correspondingly, the Islamic State also used airborne drones to drop Mortar rounds on fighting troops in the Iraqi cities of Raqqa and Mosul. In 2021, the Indian Air Force base in the contested Jammu and Kashmir valley also came under attack by explosive-laden drones. Indian authorities claimed there were no severe damages. Similarly, groups beyond the Middle East and Europe are also using smaller UAVs to counter larger state militaries. Rebels in Myanmar used small drones to counter Myanmar’s military, which has a dedicated Air Force.

The embrace of smaller UAVs is not merely a force complementing strategy; rather, it is becoming a warfare doctrine of its own where Non-Western countries are circumscribing costly Western systems by a three-pronged strategy: bleeding them through costs, overpowering in numbers, effectuating drone systems in regular command hierarchies. An American military acquisition cycle ( of ten years ) focusing on sophisticated systems costs tens of billions of dollars and requires a parallel force posture. Hence, the USA has been lethargic in responding to the UAV threat. The threat perceptions become precarious once the UAV swarm threats are witnessed against America’s forward posturing career strike groups in the context of Houthi rebels using drones to exhibit their strike capabilities in the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab Strait.

This goes on to show that drones are disruptive ( in terms of tech and military operability), and whichever state or non-state actor wields their effective use through innovation and tactics will define the conflict asymmetry of future conflicts.

To adequately prepare for the future, countries will need to move beyond mere reforms in weapons procurement ( simply increasing numbers) and, instead, focus on transformative changes in their military’s organizational structures and training methodologies. This involves increasing the flexibility of the complex, hierarchical chain of command and delegating greater autonomy to smaller battle units that can respond promptly to rapidly changing scenarios and instant threats. These units should be led by combat leaders who have undergone specialized training in AI, data systems, drone tactics, and counter-drone tactics and are empowered to make pivotal combat decisions.

Table of Contents

ToggleHammad Waleed

Hammad Waleed is a Research Associate at Strategic Vision Institute, Islamabad. He graduated with distinction from National Defence University, Pakistan. He writes on issues pertaining National Security, Conflict Analysis, Strategic forecast, and Public Policy. He can be reached at hammadwaleed82@gmail.com.