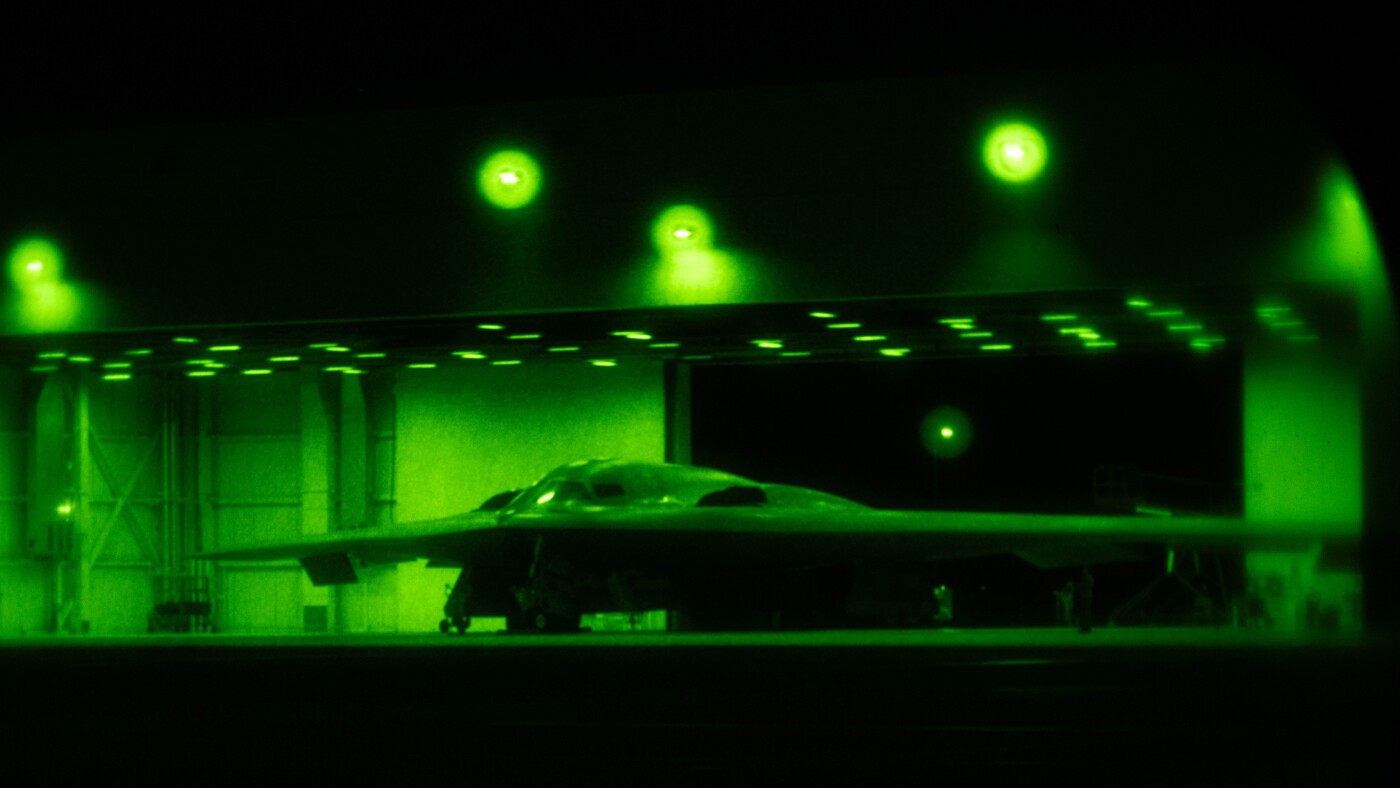

In a demonstration of unmatched stealth and precision, the United States executed one of the most audacious and technologically sophisticated air strikes during Operation Midnight Hammer. At the core of this operation was the B-2 Spirit—America’s long-range stealth bomber, whose flying-wing design, radar-evading material, heavy payload capacity, and long range enable it to penetrate deep into well-protected hostile territories for bombing operations. In its internal weapon bay, B-2 is capable of carrying up to 80 Mark 82 bombs, each weighing 500 pounds, or it can switch to a rotary launcher to deploy 16 precision-guided AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSMs), with a range in excess of 370 kilometers. However, in missions requiring sheer penetrative force, the B-2 is the only aircraft in U.S. disposal that can be armed with GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrators (MOPs)—30,000-pound bunker busters designed to destroy deeply buried and fortified structures with precision. These bombs, though lack propulsion, use advanced guidance systems combining GPS and an inertial navigation system. Traveling purely under the force of gravity, they can penetrate up to 200 feet into reinforced concrete before detonating, making them ideal for crippling hardened facilities.

On 22 June 2025, the U.S. initiated Operation Midnight Hammer to target three key nuclear facilities of Iran: Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. Two B-2 Spirits departed from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, heading westward—toward the Pacific. This flight path, comprising of observable refueling stops in Oklahoma, California, and Hawaii, misled military watchers and the Iranian intelligence into believing the bombers were headed to staging grounds in Guam or Diego Garcia. As the world’s attention shifted west, the real strike force—seven B-2 Spirits loaded with two MOPs each—departed silently to the east, flying under minimal communications directly towards Iran, undertaking multiple in-flight refueling from tanker aircraft.

Meanwhile, a U.S. Ohio class guided missile nuclear submarine (SSGN), armed with Tomahawk cruise missiles, stationed in the Arabia Sea launched over two dozen Tomahawk cruise missiles targeting Iranian air defense sites and radar stations. These land-attack missiles arrived moments after the aerial strike, coordinated to follow the B-2 bombing run. Between 6:40 and 7:00 p.m., the B-2 Spirits, protected by stealth fighter aircraft, executed their primary objective. Twelve GBU-57 MOPs were dropped on Fordow, and two on Natanz. Operation Midnight Hammer marked fthe irst-ever combat use of MOPs. Then, as silently as they came, the B-2s exited Iranian airspace and returned to base—having executed the largest B-2 operational mission in U.S. history, second in range only to post-9/11 sorties.

Despite the military success in precision and stealth, the strategic outcomes of Operation Midnight Hammer still remain ambiguous. Satellite imagery confirmed visible damage to the three nuclear facilities, but critical questions remain. Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium, reportedly stored in mobile cylinders, may have been relocated before the strike. If so, Iran could potentially resume uranium enrichment with minimal delay once its nuclear infrastructure is recovered from damage it sustained from Israeli and American strikes. Furthermore, the survivability of Iran’s centrifuges, which form the backbone of its enrichment program, is also uncertain.

Post-strike satellite imagery of Fordow revealed two clusters of likely bomb entry points and a layer of gray-blue ash over the site. U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Caine confirmed the nuclear facilities had sustained “severe damage,” though full assessment would take time – an argument also stated by Israeli officials. A leaked U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) report estimated the strikes set Iran’s program back by months, damaging but not destroying key sites, whereas the Pentagon later claimed a one- to two-year setback. Trump administration officials rejected the initial estimate, indicating Natanz, Fordow, and Esfahan were severely damaged and would take two years to rebuild. Iranian officials have also acknowledged the damage but initially argued that the Trump administration is exaggerating the damage. Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmail Baghaei admitted that the facilities “have been badly damaged,” and Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi later confirmed “significant and serious damages.” IAEA chief Rafael Grossi also noted “severe damage” but stopped short of calling it “total damage.” It worth noting that without direct access to the sites, international inspectors cannot verify the extent of destruction or the resilience of Iran’s nuclear program.

Despite achieving successful strikes, Operation Midnight Hammer has also exposed challenges associated with achieving permanent neutralization against ultra-deep, compartmentalized, and redundant underground complexes. This necessitates that future campaigns will rely on iterative, multi-sortie targeting rather than single decisive blows.

Beside U.S., few other nations either possess or are seeking to develop targeting capability against deeply buried targets. China employs DF-15C ballistic missile armed with a bunker-busting warhead. India is planning to integrate a bunker-busting payload on the Agni-V ballistic missile in future. However, even if we put aside the nuclear-conventional entanglement linked with the use of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles for bunker bunker-busting role, the use of ballistic missile instead of precision-guided bomb means that it would be very difficult to hit the intended target with precision. Thus, this poor will subsequently undermine efficiency of such operations.

Operation Midnight Hammer also signaled the scope of technological evolution in bunker-busting missions. The U.S. Air Force (USAF) is already accelerating the development of a Next Generation Penetrator (NGP) to be carried by the upcoming next-generation B-21 Raider bomber. NGP will likely be smaller, potentially powered for stand-off delivery, and equipped with advanced guidance and programmable fuzing to function in GPS-contested environments. Future bunker-busting missions will be characterized less by sheer explosive mass and more by an integrated “kill chain” that combines deception, suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD), electronic warfare (EW), cyber disruption, and precision intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) to identify vulnerable aim points. Precursor munitions, tandem-penetrator concepts, and rocket-assisted or hypersonic delivery systems are expected to further increase effectiveness while reducing platform vulnerability.

While the B-2 and MOP combination is formidable in the contemporary threat environment, the arrival of the B-21 will significantly enhance survivability, sortie rates, and operational flexibility, considering the fact that B-21 will be available in far greater number than the mere 19 operational units of B-2, enabling a larger number of bombers to participate in deep-strike missions. However, adversaries will adapt by further hardening and deepening facilities, incorporating shock isolation techniques, dispersing critical infrastructure, using decoys, and investing in counter-stealth and GPS-denial capabilities, thereby increasing the premium on stand-off precision strikes. Notably, the trajectory of U.S. policy and technological investment suggests that nuclear earth-penetrators are unlikely to return, with the emphasis remaining on conventional disruption supported by sustained operational and political pressure. In essence, the future of bunker-busting is shifting from one-off “silver bullet” strikes toward sustained, multi-domain campaigns in which stealth platforms, advanced penetrators, and integrated ISR-EW-cyber capabilities combine to keep even the most hardened underground targets vulnerable over time.

Table of Contents

ToggleAhmad Ibrahim

Author is Research Associate at Pakistan Navy War College, Lahore.